S/V Tango. Log entries 2008-9

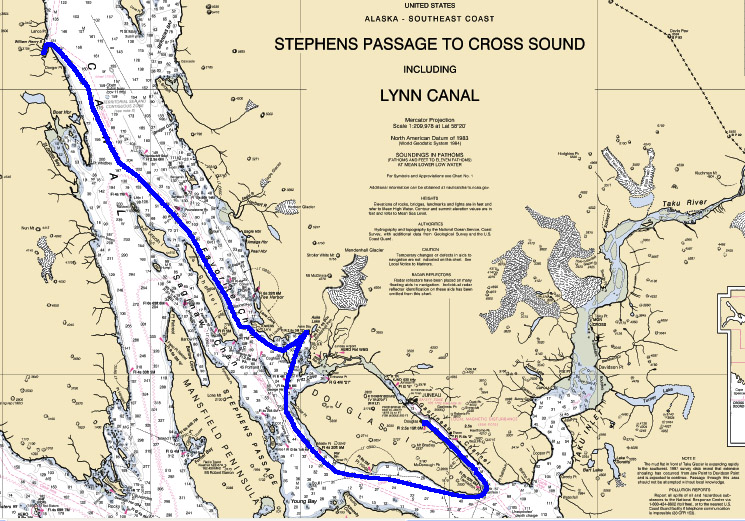

Part 8: Juneau to Skagway

July 20-26, 2009

Douglas Harbor to William Henry Bay.

7/20/09.After a couple of weeks of moorage across the channel from Juneau, Tango eased out of Douglas Harbor. Aboard were Peter Ffolliott, Margy Riggs, Dennis Todd, Jill Liberty, and Bob Guza. We motored around Douglas Island, again, to Auke Bay, where we intended to stay for a few hours and to get fuel.

The marina was busy, but a miracle happened. Mega-yachts, both sail and power, filled both sides of the breakwater. As we entered the marina, expecting to have to look long and hard for a suitable slip, a power yacht pulled away from the dock. Without hesitation, we nosed Tango in—we knew that if we circled and looked it over, some other boat would take the space. The deck crew hustled to get the fenders out and the mooring lines ready, and we tied up jubilantly.

Jill and I rode the city bus into Juneau, hoping to get a couple of packages addressed to General Delivery at the main post office. One package was there, but the other has gone into limbo. I had ordered a computer keyboard for Tango to replace one that drowned when splashed with water, but the brain-deficient shipping department at Amazon.com sent it by United Parcel Service. The U.S. Post Office won’t accept delivery from UPS. UPS does not have an office in Juneau, and no human is available via the automated phone hell that one ventures into when calling the UPS number.

When we got back to Auke Bay, the crew was inclined not to continue the voyage that day, so we stayed the night. The best coin-operated showers we’ve found on this voyage are at the Harbormaster’s office—a good long shower can be had for only 50 cents. I splurged and put in four quarters, hoping to wash away the frustration of dealing with shipping. Half the packages that have been sent to us along the way have failed to reach us for one reason or another.

7/21/09. We motored to one of the two fuel docks at Auke Bay. It was in shoal water at low tide, so maneuvering was tight. It took a lot of back-and-forth shifter and throttle work to sidle up to the dock. As we were tying up, Peter noticed the sign in the window that said the place was closed for the 2009 season. We headed for the other fuel dock just as another sailboat pulled up to it. We spun a circle in the basin to wait only to see a small power boat pull up next to the sailboat to wait his turn. I realized that we had to keep Tango between the fuel dock and the basin to keep our place in line.

Refueling a boat takes a long time. The dock attendant may take his sweet time getting to the dock, the boat may have more than one tank, the capacity may be a hundred gallons or more, and the cash transaction seems to take an inordinate amount of time. We had to hold station for half an hour before we could pull up for fuel.

We motored away from the dock, dodging boats coming from every side, and were greatly relieved to pull out of the bay and into Stephens Passage. We saw a congregation of tour boats near the shore of Favorite Channel so we headed in that direction. They were watching whales near shore, but the show was soon over as the whales submerged and didn’t reappear.

As we motored north in Lynn Canal (the longest fjord in North America), low clouds hiding the mountains, we saw an orca heading the other direction. A couple of Dall’s porpoises checked us out but didn’t stop to play—they diverted for a quick pass across our bow then resumed their sprint to the south. By mid-afternoon, we anchored in William Henry Bay, halfway between Juneau and Skagway. We arrived near high tide and expected a 24-foot tidal range, so we picked our anchor site carefully.

As we were anchoring, I noticed the bilge pump spewing a lot of water. Once the anchor was set, I pulled up the hatch in the aft cabin sole. The shaft seal was leaking—it had slipped forward on the shaft. I tapped it back into position and replaced the set screws, hoping that they’ll hold better this time.

Bob broke out his fishing gear. The first cast, he hooked a fish so big that it snapped the line and took his lure. After changing to a different reel with heavier line, he spent hours fishing off the stern, oblivious to the wind and rain. He caught several undersized halibut but no keepers.

7/22/09. We made a leisurely departure from the bay and motored north in Lynn Canal for a few hours in rain and low clouds. We knew there were mountains close at hand, but we couldn’t see them.

We anchored in a bight on the mainland west of Sullivan Island. The breeze was brisk, the rain pelted down, and Bob stood valiantly on the stern, dressed in his foul weather coat, jigging for bottom fish. He brought up a few cod, which he used to bait the crab trap. An hour or two later, we heard him exclaim “Holy shit!” as he raised the trap.

The crabby professor.

There were eight big crabs scrambling over one another. It was a CPR (Crustacean Personal Record). He let five go; he and Peter cleaned three and served the meat with a garlic and butter sauce over spaghetti noodles. I baked French bread and roasted a head of cauliflower. We broke out a bottle of champagne. It was a feast!

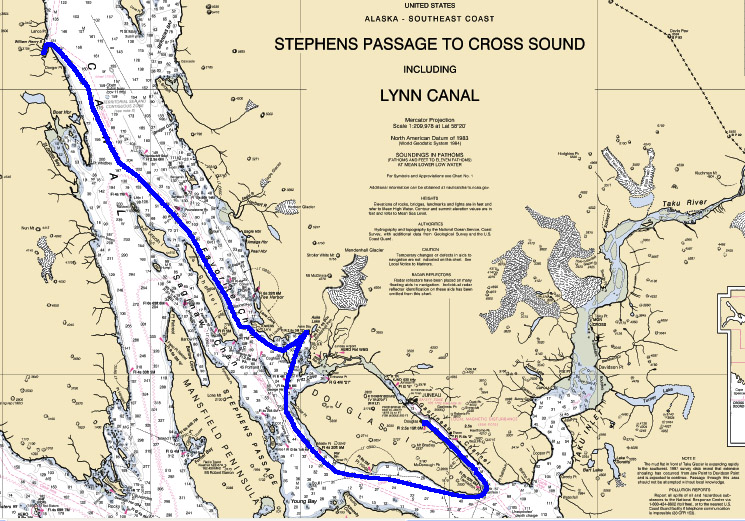

7/23/09. We dodged behind islands to reduce the swells coming from the south as we motored toward Haines. There wasn’t enough wind to sail, but it was enough to raise unpleasant waves at the end of the 60-mile fetch of Lynn Canal. When we got to Haines, it was gusting to 30 knots. With some trepidation, we nosed into the boat basin. Our concern was compounded when we saw that some of the docks were gone, a big construction barge filled half the harbor, the dock marked “transients” on the chart bore signs saying “reserved mooring only,” and the wind pushed Tango’s bow down. It took some high-adrenaline, close-quarter maneuvering to get out of the tight pocket. We nosed into a space at the end of a dock with a weathered sign “Trans,” which we assumed meant “transient moorage.” There was no power and no water at the docks—the wires and pipes had been removed.

Haines harbor facilities.

After a few hours, Joe the harbormaster came by and told us that we had to move—a fisherman was assigned to this slip. But the wind was so stiff that he soon talked himself out of his edict. The fisherman pulled into the harbor, saw us at his slip, and yelled curses at Joe, who directed him to the slip that he had wanted us to move to. He told us that he’d be in touch. The harbor was being renovated. Some of the docks had been removed, slip assignments had been changed, and room was tight.

Haines small boat basin.

Haines turned out to be a nice little town, population about 2300. It has no cruise ship dock (thank the gods), but it has a good tourist trade because, unlike most Southeast towns, it’s connected to the highway system. Its central feature is Fort Seward, a fort built in 1903 to defend the US border against marauding Canadians(!). The fort saw little action and was among the Army’s least desirable postings. It was closed in 1946. A group of WWII veterans purchased the property and established the community of Port Chilcoot, which later merged with Haines. Today, the stately white buildings house a hotel, a restaurant, and residences. We had lunch at the Fireweed Restaurant in what might once have been a barracks.

The white buildings of Fort Seward dominate the foreground.

While Bob stayed at the dock, obsessed with piscatorial pursuits, the rest of us explored the city. Harbormaster Joe stopped by again. He told Bob that we’d have to move at 4:00 PM. We assembled at the boat, ready to make the move. When the time came, the wind was just as strong, the fisherman was nowhere to be seen, and Joe again talked himself out of it. He said he’d call if we had to move.

Bob fishes for dinner.

7/24/09. I woke at 04:00, thanks to a marauding band of crows that discovered Bob’s fishing gear and crab trap on the stern, right over my bunk. They hopped all over the trap, the rigging, and the deck, their cawing and claw-clattering making sleep impossible. I threw open the hatch, popped my head out, and yelled at them. They scattered but returned in less than a minute. Especially intrigued by the bag of fish heads that Bob had saved as crab bait, they kept trying to pull it out of the trap. They stole the cheese off his fish hooks. They crapped on the deck, the cabin, the hatch, and the brightwork before they left. After trying a few times to chase them off, I finally gave up and let them have their way as I tried to get back to sleep.

I was determined to move Tango to the right slip as soon as the fisherman vacated it. But he didn’t show up until noon, and by that time the wind had risen again, and Joe decided we could stay where we were.

I did laundry, got a haircut, and visited the Hammer Museum. The museum started as a hobby that grew out of control and is now open to the public. The small building has 1500 hammers on display, ranging from a large stone hammer from ancient Egypt to curiosities such as patented multi-claw hammers to specialized hammers for cobblers and ironworkers, and another 6,000 in storage and rotating exhibits. I found it fascinating, but before I was through my eyes glazed over from information overload. Who knew there were so many different hammers?

The Hammer Museum.

A giant hammer being installed at the Hammer Museum.

Patented hammers and the cover pages of their patent applications.

Blacksmiths' hammers.

When we invited Bob to put down his fishing pole and visit the Hammer Museum, he was deeply conflicted. What real man could turn down a chance to see a museum devoted to the ultimate masculine tool? A real fisherman could, as it turned out. He wanted to cook fish tacos for dinner and was determined to catch the requisite fish. He was successful, and although the sculpins he caught were small, he was able to filet and fry enough that we had a very tasty dinner.

The tides are enormous here. At mid-morning, with a low tide of minus 4.0 feet, the ramp from the floating docks to the shore was at such a steep angle that it was a real chore to climb. The boat basin becomes alarmingly small when the tide is that low. The tide rose 23 feet over the next six hours, driving away the welders who were working on the tidal grid near the ramp.

Haines tides.

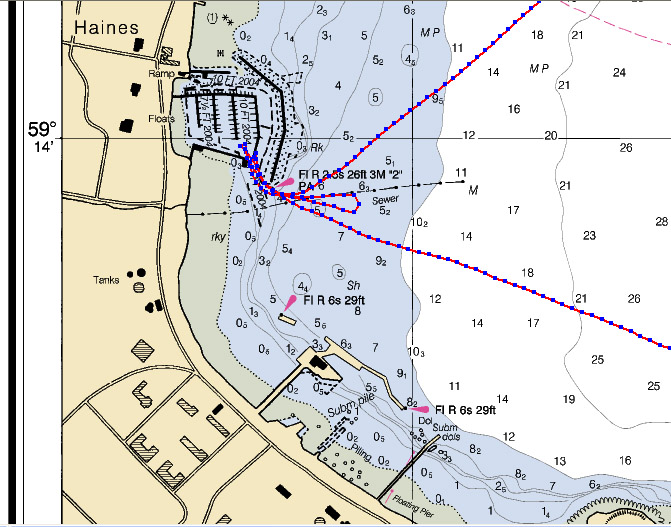

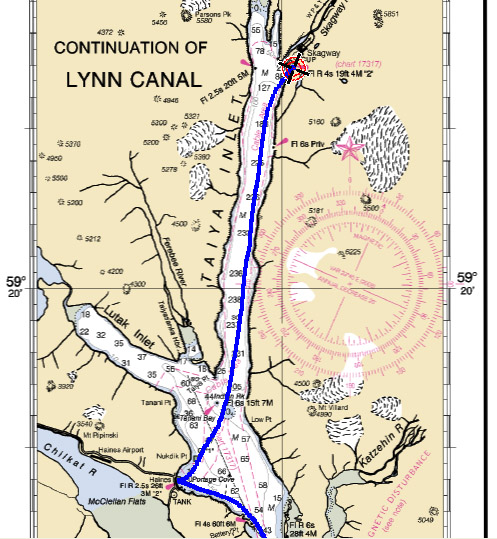

7/25/09. We got up early to avoid the wind and motored 13 miles to Skagway, the head of Lynn Canal and the northern terminus of the Inside Passage. We celebrated reaching 59 degrees 27 minutes north. I had called ahead to reserve a slip, so we were sure we had a place to land, unlike Haines. There was little wind and although the basin is tight, it was an easy entry.

Margy found that seats were available on the afternoon train of the White Pass & Yukon Route, a narrow-gauge railway built in the late 1800s. The vintage diesel locomotives and refurbished parlor cars climb a steep grade, up to 3.9 percent, winding their way to the international border and on to the Yukon. The excursion train, however, went just beyond the border before returning to Skagway.

This cantilevered steel bridge was in use until it was replaced with a shorter bridge and a tunnel in the 1990s.

It's a good thing that the bridge was abandoned.

The Mounties' shack at the international border.

The railroad paralleled the foot trail used by gold-seekers in the 1890s.

Instead of turning around, the train went onto a siding, the engines decoupled and passed the passenger coaches on the main track and coupled to the other end of the string of coaches. Everybody aboard was told to stand up, flip their seat backs over so they were facing the other direction, and change seats with the people sitting across the aisle so the passengers without a view on the way up would get the view on the way down. And views there were. The mountainside was so steep that the railroad grade clung to the slope, the rapids of the river were visible below, and sharp peaks surrounded us on every side.

The rocks were ground smooth by glaciers.

This rotary snow plow was built in 1899.

On May 27, 1898, construction began on the railroad grade at Skagway. Work continued through the winter (I can’t imagine how); by July 29, 1900, the railroad reached Whitehorse, Yukon Territory, some 110 miles away. By the time it was completed, the gold strikes that had drawn tens of thousands of miners to the Yukon and that had inspired the construction of the railroad had lost their allure and the boom had died.

The railroad operated steadily for the better part of a century, carrying freight and passengers to and from the head of navigable waters in the Yukon. The company pioneered the concept of containerized cargo, which now dominates freight transportation around the world. They built the first container-cargo ship, the first dockside container cranes, and the first train cars built specifically for containers. In 1982, the mines that had provided the greatest part of the railroad’s business closed, and the railroad suspended operations indefinitely. But tourism grew, fueled primarily by the cruise ship industry, and in 1989 the railroad opened for summer excursions.

Skagway small boat basin.

Skagway small boat basin.

Skagway is much like Ketchikan in that it is dominated by cruise ships. Two big ships were docked when we landed; two others took their place the next day. Each can disgorge 5,000 passengers looking for goods, services, and entertainment. Skagway has become a theme park of the old west. Historic buildings have been repaired, restored, repainted, and occupied by gift shops, upscale stores, museums, and fur boutiques. There must be more than a dozen jewelry stores, all appealing to cruise ship passengers. One has to look hard to find the stores where the 800 locals shop and the neighborhoods where they live.

The Alaska Brotherhood hall, now a tourist information center.

After the train returned to Skagway (Tlingit for “windy place”), we walked around the town just like thousands of other tourists, except that we didn’t go into the jewelry stores. After buying a few souvenirs and some ice cream, we headed back to Tango, exhausted from so much fun.

Skagway is known as the garden center of Southeast Alaska. The citizens take the responsibility of living up to the title.

Many tours are available in Skagway.

Skagway has too many jewelry and fur stores to be authentic.

--Dennis Todd

Photos by Dennis Todd and Peter Ffolliott.

| home | downloads and links |

| log entries | dinghy construction |

| tips for crewmembers | travel options |